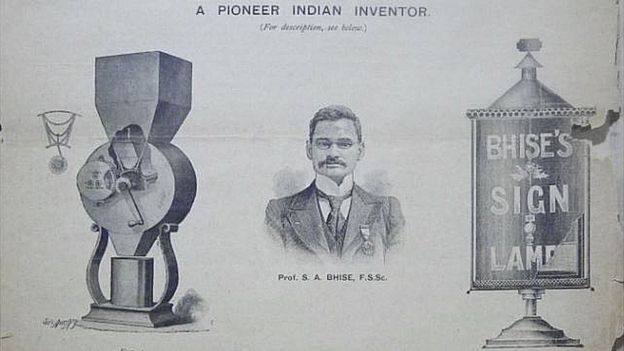

His countrymen hailed him as the “Indian Edison” after the famed American inventor.

International investors believed that his inventions could revolutionise the global printing industry; and he won the support and admiration of leading Indian nationalists.

And yet Shankar Abaji Bhisey, a pioneering Indian inventor of the 19th Century, is all but forgotten today. How has this come to pass?

Bhisey shot to fame when India, now a hub of innovation and scientific talent, possessed hardly any institutions for nurturing scientists, inventors, and engineers.

He was entirely self-trained, emerging from obscurity and – unfortunately – sinking back into it after his death.

Bhisey grew up in colonial Bombay’s (now Mumbai) crowded side streets, where he spent his days poring over Scientific American magazines.

“I owe everything to the mechanical education I received from that American magazine,” he told a Brooklyn newspaper many decades later.

He founded a scientific club in Bombay and, by his early 20s, began designing a slew of gadgets and machines: tamper-proof bottles, electrical bicycle contraptions, a station indicator for Bombay’s suburban railway system.

His break came in the late 1890s when he heard about a competition, organised by a British inventors’ journal, to design a machine for weighing groceries.

Relocating to London

In a fit of inspiration between three and seven o’clock one morning, he sketched out a blueprint – and won, beating all the British contestants.

By now, Bombay’s administrators had taken notice of the bright Indian inventor. They supported Bhisey’s desire to relocate to London to woo investors. Bhisey resolved to his Bombay friends that he would “not return home unless I either make a success or spend till my last pound”.

And so began a remarkable phase of his career, when the young inventor was drawn into anti-colonial circles in the very heart of empire.

Bhisey arrived in London with a letter of introduction from Dinsha Wacha, the Bombay-based secretary of the Indian National Congress.

In addition to steering India’s premier political organisation, Wacha was a shrewd businessman with an eye for technical talent.

Thus, one morning in London, Bhisey delivered Wacha’s letter to Dadabhai Naoroji, a nationalist colleague who also had a long commercial career in England.

Naoroji, impressed with Bhisey’s growing list of international patents, readily agreed to form a business syndicate. After inking an agreement, he gave Bhisey a reading list on the Indian nationalist agenda.

From a damp and cold workshop in north London, Bhisey set toto work.

Dazzling array of inventions

He designed an innovative electronic signboard which was exhibited at the Crystal Palace in London and eventually adopted in stores in central London, Wales, and possibly Paris.

He informed Naoroji of a dazzling array of new inventions: kitchen gadgets, a telephone, a device for curing headaches, and an automatically flushing toilet.

In 1905, he even patented a prototype push-up bra, a “bust-improving device” for “imparting a graceful and full appearance to the bust” (A bashful Bhisey seems to have not told Naoroji about this invention).

But Bhisey’s most significant invention concerned printing: the Bhisotype, a typecaster that promised to revolutionise the printing industry.

It quickly and cheaply produced metal types – used to print books and newspapers -and it did so faster and more efficiently than the industry leaders of that time.

At this point, Naoroji told Bhisey that he needed to find more deep-pocketed investors. He thus directed the inventor to his friend Henry Hyndman, the “father of British socialism”.

Hyndman was a disciple of Karl Marx and one of the fiercest British critics of Indian colonialism. He assailed London’s “profit-mongering classes”. Incredibly, anti-capitalist Hyndman was himself a prominent businessman with wide-ranging printing industry contacts. He promised to raise a whopping £15,000 for the Bhisotype.

This was where things started to fall apart.

Bhisey spurned an offer from a printing industry giant, the Linotype Company, to buy out the Bhisotype. He spent excessive time fine-tuning his machine, confident about Hyndman’s promised financing.

But, by 1907, Hyndman realised that he could not raise these funds. Naoroji’s reserves dried up the following year. In December 1908, a heartbroken Bhisey had to cease work and sail back to Bombay, having truly spent “till his last pound”.

And here he caught a second wind.

Aboard his Bombay-bound steamer was Gopal Krishna Gokhale, a prominent Congress leader. Bhisey dazzled Gokhale with his typecaster.

Yet one aspect of his legacy is worth remembering.Until his death, Bhisey kept alive the anti-colonial spirit kindled by his former financiers.

In London, he joined Naoroji and Hyndman in demonstrations and meetings; in New York, he championed Gandhi’s ideas and hosted visiting Indian nationalists.

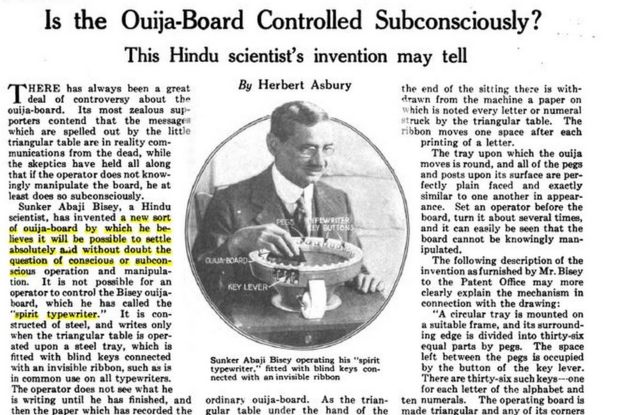

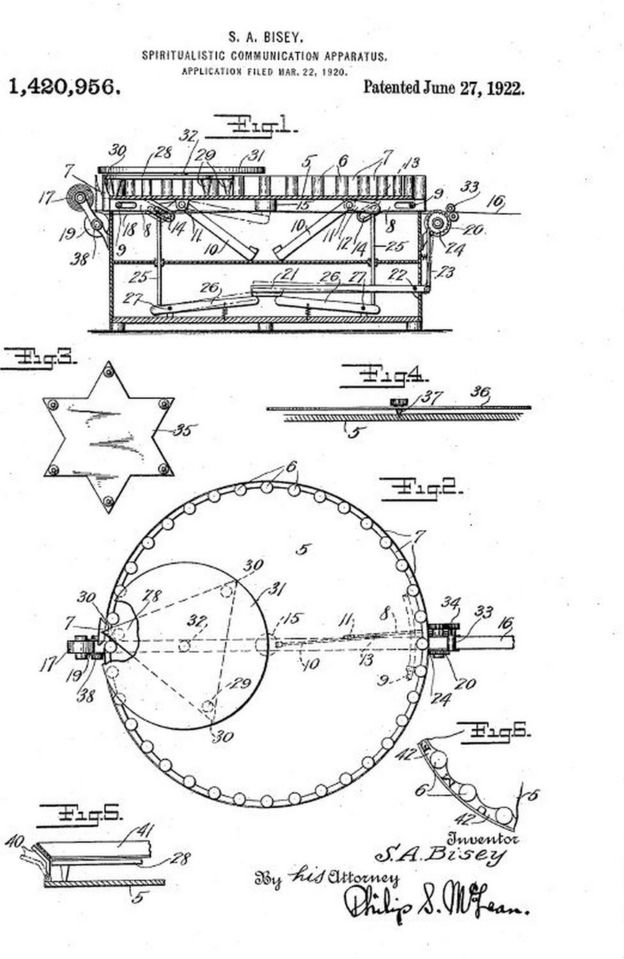

From India to Britain and America, Bhisey merged progressive politics with science. No “spirit typewriter” is necessary to divine the importance of such a legacy today.

(Dinyar Patel is an assistant professor of history at the University of South Carolina)

Siurce:https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-india-48905151

Readers like you, make ESHADOOT work possible. We need your support to deliver quality and positive news about India and Indian diaspora - and to keep it open for everyone. Your support is essential to continue our efforts. Every contribution, however big or small, is so valuable for our future.