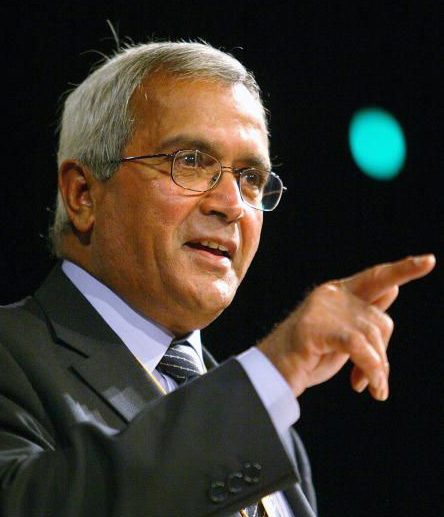

Noting that “£1 billion can buy 10 votes for the length of this Parliament,” and, “[t]he same amount could improve our prison system and make it fit for generations to come for a very long time,” Lord Dholakia asked “a fundamental question: do prisons really rehabilitate inmates?”during the third day of the Humble Address to the Queen’s Speech. Answering his own rhetorical question Lord Dholakia spoke of his dismay that “the Government have certainly sacrificed some key reforming measures that should have been included in the gracious Speech.”

Highlighting his point, Lord Dholakia stated: “one such issue, referred to by my noble friend Lord Paddick, is the problems in our prison system.” This is an issue Lord Dholakia has championed during many parliamentary sessions and there is, as he pointed out: “[t]he need for greater efforts to promote prisoners’ rehabilitation is clear from even the most cursory look at reoffending rates. Some 44% of adult prisoners, 59% of short-term prisoners and 69% of juvenile prisoners are reconvicted within a year of their release—an unending cycle that continues to repeat itself on a regular basis.”

Stating how the ‘revolving door’ sees inmates continually return to prison, Lord Dholakia said: “all too often their pro-criminal attitudes are unchanged. Imprisonment causes many prisoners to lose their accommodation, their jobs and, sometimes, their families.” This has often meant that: “[o]n release they are, therefore, more likely to be jobless, homeless and without family support, all of which increase the risk of reoffending;” and more importantly: “research and experience tell us a great deal about successful approaches that can reduce these dismal reconviction rates,” Lord Dholakia stressed.

Asking if the Minister would “look at the Ofsted inspection of prison education provision and Unlocking Potential, the report produced by Dame Sally Coates?” that recommended improvements to prison facilities Lord Dholakia continued “we know that focused offending behaviour programmes can reduce reoffending. These programmes can change attitudes to reoffending and improve empathy with victims.” Listing the way this helps “offenders to restrain impulsive and aggressive behaviour, to resist peer pressure and to recognise and manage the trigger situations that lead them to offend,” Lord Dholakia emphasised the most important factors were “getting released prisoners into jobs cuts reoffending; providing educational opportunities reduces reoffending; providing stable accommodation on release cuts reoffending; maintaining family ties cuts reoffending; and effective drug rehabilitation dramatically cuts reoffending.”

Even so, Lord Dholakia maintained that: “we need to go much further than [the report] and ensure that every prisoner who needs a programme to tackle his offending behaviour or an intensive drug or alcohol treatment programme can get on to one.” Showing the difficulties there are Lord Dholakia commented on the importance of domestic violence courses saying: “waiting lists are often far too long. For example, it can take two years for a prisoner assessed as needing a programme to tackle domestic violence to get on to one. That cannot be good enough if the strategy is to stop that sort of reoffending on release.” Sadly, the wait is not surprising when: “we now have 148 prisoners in England and Wales for every 100,000 people in our general population compared with 101 in France and 76 in Germany.”

Questioning if: “[w]e are not twice as criminal as Germany, so why do we need to use prison twice as often? Lord Dholakia pointed out “[s]o many prisoners reach the end of their sentence without work being done that could reduce their risk, and victims of crime suffer as a result.” This is not difficult to understand when: ” as a result of our high use of imprisonment, much of the prison system is overcrowded, overstretched and cannot provide effective rehabilitation for all its prisoners,” he stated with equanimity.

Finishing off, Lord Dholakia urged “the Government to think again about their regrettable decision to drop the prison-related elements of their previous Prisons and Courts Bill from the programme for this Session. Those provisions amounted to just 22 clauses.” His reasoning is underpinned by the grim findings of “[t]he reports of the Chief Inspector of Prisons into Brixton prison published this month illustrates these problems [in prisons] graphically.” The report found that, “. two-thirds of prisoners said that they had felt unsafe in the prison. Levels of violence had increased and self-harm incidents had quadrupled since the last inspection of that prison.” This was a very strong reason why Lord Dholakia believed wholeheartedly that “prison should be removed as an option for many lower-level offences and sentencing guidelines should scale down the length of sentences except for the most serious offences and the most dangerous offenders.”

If the 22 clauses were “reintroduced in a short prisons Bill,” Lord Dholakia believed “there would be strong all-party backing to ensure its safe passage through this Parliament,” and most importantly “the prospects for reducing the high number of crimes committed by released prisoners would be much better.”

Readers like you, make ESHADOOT work possible. We need your support to deliver quality and positive news about India and Indian diaspora - and to keep it open for everyone. Your support is essential to continue our efforts. Every contribution, however big or small, is so valuable for our future.